In light of the surging evidence of climate change, the European Union (EU) has made climate policy a European key priority over the years by committing itself to ambitious goals (Siddi, 2020, p. 4). In December 2019, the European Commission adopted the European Green Deal (EGD), which set the target of achieving climate neutrality by 2050. The EGD has introduced an array of methods and policies directed at transforming the European economy and society through decarbonization in a sustainable, just, and inclusive way (Fetting, 2020, p. 4). With this pioneering initiative, the EU does not only seek to mitigate the effects of climate change locally but has also positioned itself as a global leader in climate mitigation (Sanahuja, 2025, p. 343; Siddi, 2020, p. 4). These efforts have allowed a new standard to be set in which climate action is prioritized over economic growth (Eckert, 2021, p. 81). However, recently there has been a noteworthy shift in the EU’s climate narrative, as its commitment is being challenged by economic concerns (Stoian et al., 2023, p. 16).

This shift has become especially apparent in the implementation of the Clean Industrial Deal (CID) in February 2025. The Commission clearly signals that the EU’s agenda will be dominated by economic security, competitiveness, and strategic autonomy until the 2029 elections (Adolphsen, Könneke & Schenuit, 2024, p. 2). The EU’s shift in focus on protecting the economy accompanied by the CID’s launch raise questions about the EU’s priorities. While the EGD emphasizes the urgency of climate action and prioritizes a green transition rooted in an “environment first” narrative, the CID places greater emphasis on economic competitiveness, advancing an “economy first” narrative, which appears to reverse the EGD’s intention (Adolphsen, Könneke & Schenuit, 2024, p. 2; Eckert & Kovalevska, 2021, p. 1). This shift leads to the research question: How have internal and external political pressures influenced the EU’s shift toward an ‘economy-first’ framing in climate policy since the implementation of the European Green Deal?

Answering this question is of significance on social and academic levels. Socially, the EU’s climate policy has a direct impact on global climate change and the EU’s economic stability, thus affecting every EU citizen (Chateau, Miho & Borowiecki, 2023, p. 24). A shift in priorities could have far-reaching consequences for the balance between climate mitigation and economic stability and competitiveness. It is therefore particularly relevant to identify and examine the causal mechanisms behind this shift, because its understanding helps clarify why the EU’s longstanding prioritization of climate mitigation was disrupted and what this means for future policies.

Academically, while existing studies have explored the EGD’s set targets and its economic implications (Sikora, 2021, p. 690), less attention has been paid to the conditions under which economic concerns gain priority over climate commitments. Moreover, due to its recent implementation the CID remains underexplored, leaving a significant research gap. This study will address these knowledge gaps, by offering insights into the geopolitical and institutional factors influencing the EU’s discursive shift in climate policy, thereby academically contributing to a deeper understanding of policy change in EU governance.

To address the research question, the upcoming sections of this thesis will be structured in the following manner. First, the existing literature about the EU’s shift in climate policy framing as well as the political pressures that might influence this shift will be examined, before establishing a link between the two variables. Next up, the hypothesized causal mechanisms will be outlined, providing the theoretical expectations for the analysis of this thesis. Afterwards, the methodology and research design will be elaborated on and, accordingly, the empirical data will be analyzed and discussed. Lastly, the thesis will reflect on the results and conclude.

Theoretical Discussion and Framework

The main objective of this thesis is to examine the hypothesized causal mechanisms between internal and external political pressures and the European Union’s discursive shift of the European Green Deal from an “environment-first” to an “economy-first” framing. The theoretical framework will commence with a conceptualization of the key terms, which are internal and external political pressures as well as the framing shift in EU climate policy. Subsequently, a discussion of the theories creating a link between political pressures and the EU’s framing shift of the EGD will follow. This theoretical discussion will lay the groundwork for the investigation of the causal mechanisms behind the hypothesized link of the two variables. Finally, the theoretical expectations for the causal mechanisms, rooted in the discussion of existing literature, will be formulated.

Internal and External Political Pressures

To properly answer the research question, its variables must first be conceptualized. To begin with, political pressures are essential to define as they are ever present in the policy making landscape (Jesus, 2010, p. 71). However, within political sciences no direct definition for political pressures has been established (Potters & Van Winden, 1990, p. 63), although several scholars have provided influential contributions. For instance, Bartolini (2024) refers to political pressures as structures that “do not act, but ‘condition the acting’, namely the ‘orientations’ of the actors and their ‘choices’” (p. 4). This means that despite not actually causing actions, political pressures shape the decisions and strategies of political actors by influencing their orientations and available choices. Potters and Van Winden (1990) add to this discussion by determining which factors must be present within a comprehensive conceptualization. They argue that defining political pressures must include the assumption that “the intentionto influence should be present” (p. 63), excluding “behaviour that unintendedly or as a ‘by-product’ affects the behaviour of political rulers” (p. 63). However, the degree of success must be left open within a comprehensive definition. While Potters and Van Winden’s (1990) argument of intentionality is especially relevant for understanding internal political pressures, such as lobbying and voting pressures, it is less applicable to external political pressures, such as geopolitical or geoeconomic developments, as they do not have an explicit intention to influence EU decision-making. Therefore, this thesis adopts a broader conceptualization of political pressures, which draws on Bartolini’s (2024, p. 5) view, that political pressures are causally significant and thus operate as causal factors influencing governmental actors’ choices and ways of thinking.

However, in context of this thesis it is nonetheless of utmost importance to differentiate between internal and external political pressures. As emphasized by Niemann (2006, pp. 262, 279), supranational decision-making is not only influenced by structural pressures from within the supranational institutions and domestic pressures from national interest groups, but it is also severely affected by external challenges, such as geopolitical and geoeconomic developments.

When it comes to internal political pressures, it is of key importance to consider the concept of multi-level governance, which notes that the EU’s decision-making and its narrative are subject to supranational institutions, as well as national interests and various interest groups (Knill & Liefferink, 2013, p. 119). Thus, internal political pressures comprise acts intended to change the behavior of governmental actors by affecting the public’s perception of the actors’ expected behavior (Potters & Van Winden, 1990, pp. 64-65). This includes actions, in which interest groups aim at influencing the political process of decision-making from within by having their spokespeople be elected to the institutional bodies and consequently shape its decision-making (p. 65).

Contrastingly, Cohen (1990) argues that political interests and choices “ultimately are shaped and influenced by the constraints and opportunities of the international economic structure” (p. 267), which exemplifies external political pressures. It is of significance, as the issue of external political pressures has long been central to political discourse, with policymakers aiming to create conditions that help the (supra)national economy respond to globalization and rising international market competition (Leichter, Mocci & Pozzuoli, 2010, p. 6).

Moreover, scholars highlight the interlinkage of internal and external political pressures. For instance, Potters and Van Winden (1990) emphasize that external political pressures also include actions in which “an interest group points at certain (dis)advantageous consequences of government behaviour due to other agents” (p. 64). Thus, external pressures are oftentimes mediated through internal actors, who point out how global developments could impact supranational matters, thereby influencing political decisions from within. Accordingly, Milner (1988, p. 292) claims that the consequences of external political pressures are in fact internal, since they impact national interest groups’ policy preferences, not supranational policy instruments.

Consequently, considering each condition established by the existing literature, this thesis defines political pressures as structures that condition the orientations, choices, and actions of political actors through, both, mechanisms from within political systems, and mechanisms arising from changing global contexts.

Framing Shift in EU Climate Policy

To investigate the European Union’s shift in climate policy framing, we must first understand what the concept of framing entails and how it impacts decision-making. In this context, Entman’s (1993) Framing Theory will be applied, which defines framing within political contexts as the process of“[selecting] some aspects of a perceived reality and [making] them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described” (p. 52). Thus, by emphasizing certain elements over others, framing shapes how certain issues are interpreted and acted upon by people and institutions. It is of importance, as it influences not only how policy problems are understood, but also which issues are prioritized on the political agenda and which solutions are considered legitimate in the policy-making process (Kangas, Niemelä & Varjonen, 2014, p. 77).

The question of how framing influences policymaking has been widely explored in the EU’s context (Domorenok & Graziano, 2023, p. 9). Applying Framing Theory to the EU’s framing shift of the European Green Deal reveals that it was initially introduced as prioritizing environmental sustainability, as it emphasized climate change mitigation, reducing carbon emissions, and tackling ecological challenges (Stefanis et al., 2024, p. 1). The EGD’s original framing invoked an urgent, moral imperative to act on climate change (Gerken, 2023, p. 137). Central to this policy initiative is the achievement of climate neutrality by 2050 through an array of measures, policies, and legal regulations (Fetting, 2020, p. 4; Siddi, 2020, p. 4). This includes, for example, the introduction of the Emissions Trading System, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, the Just Transition Mechanism, the promotion of a circular economy and the Farm-to-Fork Strategy (Fetting, 2020, pp. 5, 6, 12). Each of these measures reflect the centrality and priority of sustainability and the environment (Stefanis et al., 2024, p. 1).

However, this framing has evolved since. The implementation of the Clean Industrial Deal in 2025, as an industrial policy introduced under the EGD, shows a clear shift in priorities (Adolphsen, Könneke & Schenuit, 2024, p. 2, 6). According to Cornillie et al. (2025), the aims of the CID are “to create a business case for Europe’s clean industrial transformation, thereby focusing on six drivers: affordable energy, lead markets, financing, circularity and access to materials, global markets and partnerships, and skills” (p. 3). The CID emphasizes the promotion of and investing in net-zero industries, it simplifies environmental regulations introduced by the EGD and aims to bring down energy prices for industrial sectors, ultimately promoting economic competitiveness and stability (Hermwille et al., 2025, p. 6). It thus embodies a strategic response to internal and external political pressures and reflects a more pragmatic mindset by highlighting opportunity, innovation, and economic advantage (p. 5).

This strategic pivot reflects a shift in framing of European climate policy, in which economic competitiveness, resilience, and leadership in green technologies are not referred to as tools to achieving environmental goals anymore, since they have become central objectives themselves (Adolphsen, Könneke & Schenuit, 2024, p. 2). Thus, instead of aligning the economy with their ambitious climate agenda, the CID reflects EU actions that align environmental action with economic priorities. Linking these findings back to Entman’s (1993, p. 52) definition of framing, it becomes apparent that the EGD’s reframing occurred on all four levels of the Framing Theory. To begin with, the problem definition has been redirected from highlighting the climate emergency as primary issue to emphasizing the EU’s decline in industrial competitiveness (Adolphsen, Könneke & Schenuit, 2024, p. 2, 6). Furthermore, the causal interpretation went from the increasing public demand for climate mitigation (Domorenok & Graziano, 2023, p. 12) to the emphasis of both internal and external political pressures (Adolphsen, Könneke & Schenuit, 2024, p. 2; Knill & Liefferink, 2013, p. 119). Moreover, the moral assessment evolved from a moral obligation of saving the environment for future generations (Gerken, 2023, p. 137) to shielding European prosperity (Adolphsen, Könneke & Schenuit, 2024, p. 2). Finally, the suggested course of action has switched from carbon emission reductions (Eckert, 2021, p. 81) to supporting European industrial competitiveness (Adolphsen, Könneke & Schenuit, 2024, p. 2).

Causal Mechanisms

Due to the European Union’s framing shift of the European Green Deal, scholars are hypothesizing which triggers could have caused this transformation. While some believe that external political pressures have been instrumental in this shift, others claim that internal political pressures were the primary drivers. The following section will explore both sides of the debate to link the variables and investigate the potential causal mechanisms.

Firstly, various scholars see the 2022 Energy Crisis as a trigger for the EU’s discursive shift. For instance, Goldthau and Youngs (2023, p. 121) state that the crisis has accelerated the EU’s green transition by highlighting the need for energy independence and thereby increasing support for the energy transition. The authors argue the EU’s increased focus on energy security enabled it to prioritize advancements in renewable energies as a means to enhance energy sovereignty and economic competitiveness, and to reduce vulnerabilities from energy dependencies. Other scholars claim that the sudden halt of Russian fossil fuel imports harmed Europe’s energy-intensive industries, causing them to pressure the EU to reduce energy costs and create subsidies (Sgaravatti, Tagliapietra & Zachmann, 2023, p. 16). In turn, Fabra (2023, p. 3) contends, the EU has adopted a more pragmatic tone, by placing more emphasis on the economic benefits of the green transition as part of the EGD. The need to stabilize energy prices and protect European industries has thus led to measures that put economic stability and competitiveness as the priority, using the EGD’s green transition as a tool to achieve it (p. 4).

Furthermore, scholars believe that geopolitical competition as external political pressure has a significant influence on the EU’s increasing economic priority. For instance, Cornillie et al. (2024, p. 4) argue that although the EU is a global leader in green technology innovation, Chinese capacity is becoming increasingly competitive, taking away markets for European products. Furthermore, the United States Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has exacerbated fears amongst EU members that European green technology companies will relocate to the US to gain from subsidies and lower energy costs (Kleimann et al., 2023, p. 3421). Thus, rising concerns about the EU’s position in the global economy have created a sense of economic urgency (Martini et al., 2024, p. 9). European policymakers are increasingly putting emphasis on industrial policy, seeing it as a necessary response to global competition. This highlights a shift from environmental mitigation to save the climate towards climate mitigation to maintain a strategic advantage.

On the other hand, political pressures from within the EU also play a key role. As noted by Knill and Liefferink (2013, p. 119), the EU’s climate policy is subject to multi-level governance, so the supranational institutions, but also national interests and European interest groups. For instance, the radical right massively gained electoral support in EU member states over the years, becoming especially apparent in the 2024 (EP) elections, where the extreme right political groups European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), Patriots for Europe (PfE), and European Sovereignists Network (ESN) significantly increased their representation (Mudde, 2024, pp. 126-130). Ćetković and Hagemann (2020, p. 3, p. 5) emphasize that the radical right’s anti-climate narrative is rooted in the assumed economic burdens that come with climate policies. The polarizing measures of the EGD have been leveraged by radical right parties, contributing to their electoral successes on national and European levels (Otteni & Weisskircher, 2022, p. 1116; Timofejevs, 2020, p. 3; Yazar & Haarstad, 2023, p. 9). Yazar and Haarstad (2023, pp. 8-9) find that radical right parties engage in a combination of discursive and institutional tactics to delay and block climate policies. These include politicizing climate change, engaging with local interest groups and social movements to build up legitimacy, and actively undermining institutions responsible for climate mitigation measures—thereby pressuring the EU to adjust the EGD.

Lastly, Bhandari and Dijkstra (n. d., p. 15) argue that business advocate groups lobby in the EU for economic competitiveness and stability. Gullberg (2008, p. 2971) adds that European business organizations prefer to lobby key actors in the Commission over the EP and the Council of the EU. Under the concept of strategic framing, these advocate groups lobby for industrial leadership as a solution by presenting technical advancements, instead of regulations to reduce carbon emissions, as the main tools for combating climate change (Schlichting, 2013, p. 505).

Each of these internal and external factors is thought to have contributed to the EU’s discursive shift from an “environment first” to an “economy first” narrative. But how can the causal mechanisms between these factors and the EU’s discursive shift be analyzed comprehensively?

Theoretical Expectations

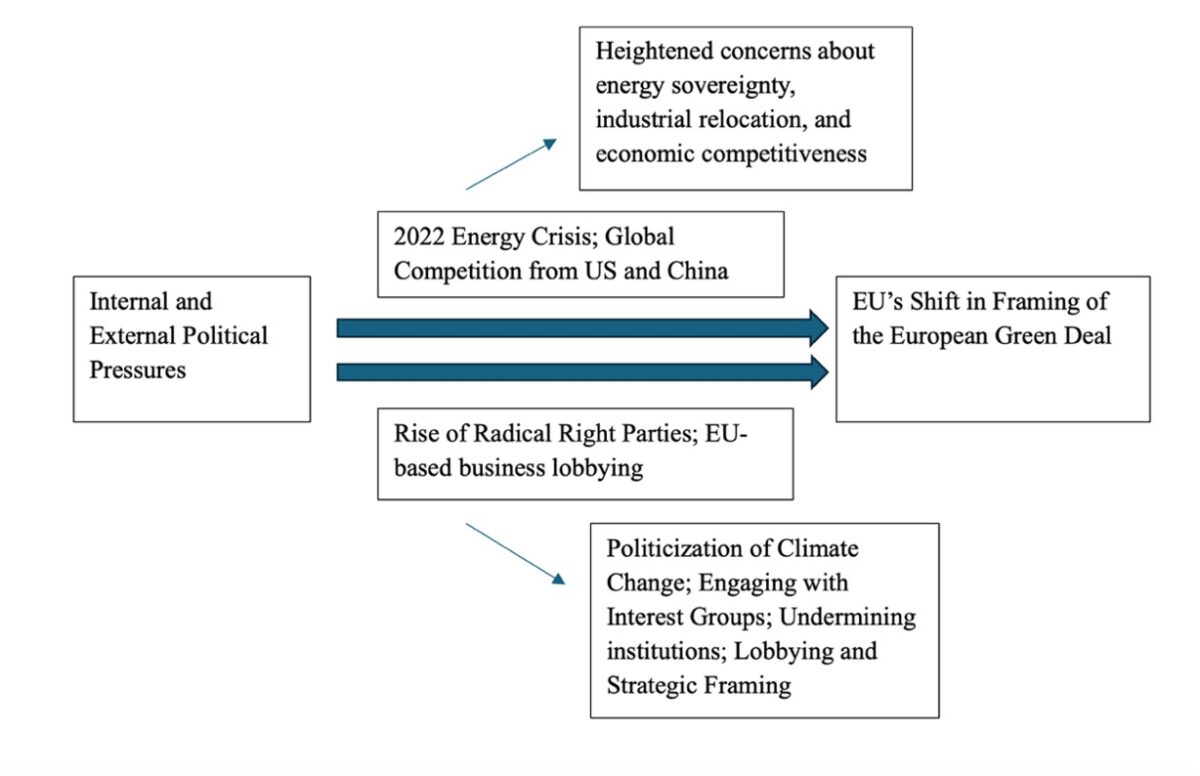

Based on the existing literature, the previous section has established the hypothesized causal mechanisms between the political pressures and the European Union’s framing shift regarding the European Green Deal. To properly analyze the research question, the causal mechanisms must be properly specified. Thus, this section aims at clarifying the causal mechanisms, elaborating on the adopted theoretical lens, and stating clear theoretical expectations. An illustration of the summarized causal mechanisms can be found in Figure 1.

This thesis examines two distinct causal mechanisms that lay behind the EU’s shift in framing of the EGD. Firstly, the study expects that external political pressures, such as the 2022 Energy Crisis (Fabra, 2023; Goldthau & Youngs, 2023; Sgaravatti, Tagliapietra & Zachmann, 2023) as well as growing geoeconomic competition (Cornillie et al., 2024; Kleimann et al., 2023; Martini et al., 2024), acted as triggers for the EU’s shift in climate policy discourse towards an economy-first framing. Through heightened concerns about European energy sovereignty, industrial relocation, and lessened European economic competitiveness, EU policymakers have changed their discourse, reframing climate policy from a response to climate change to a way to safeguard the EU’s economic and geopolitical interests. Moreover, the study expects internal political pressures, such as the rising influence of the radical right (Otteni & Weisskircher, 2022; Timofejevs, 2020; Yazar & Haarstad, 2023) and EU industrial lobbying (Bhandari and Dijkstra, n. d.), to have triggered responses of EU institutions through the politicization of climate measures, an emphasis on economic burdens for citizens and businesses, and an active undermining of such measures. Thus, by actively pressuring EU policymakers, these interest groups have caused a reframing of the EGD to address economic concerns. Overall, this thesis expects that both internal and external political pressures triggered the EU’s discursive shift, positioning the EGD as a tool for economic competitiveness rather than for climate mitigation.

To analyze these causal mechanisms behind the EU’s shift in framing of climate policy, this thesis combines discursive institutionalism (DI) and historical institutionalism (HI) as a theoretical lens. To begin with, DI intends to demonstrate the shaping influence of ideas and discourse or, stated otherwise, the way in which discourse shapes political decision-making and brings about change (Schmidt, 2008, p. 306). It focuses on the political actors’ use of speech to establish, contest, or validate policy narratives within institutions (p. 322). When applying DI to this thesis, it enables an analysis of how the shift in the EU’s framing to an economy-first narrative in climate policy is constructed, justified, and communicated by key EU political actors.

However, DI alone is not a sufficient theoretical lens, as it only explains the “how” behind the EU’s framing. Therefore, HI will serve as a supplementary theoretical guide to explain “why” this shift occurred. To specify, this thesis applies critical juncture analysis as part of HI. Critical juncture analysis allows for an examination of the political origins that lead to reform and have a lasting impact on political decision-making within institutions (Capoccia, 2015, p. 147). Critical junctures are defined as points in time when political agency and choice can play a crucial causal role in determining an institution’s course of development since it is unclear what the future of an institutional arrangement will hold (p. 148). When applied to this thesis, critical juncture analysis thus allows for an identification of critical junctures that have caused the discursive shift and an examination of the causal mechanisms that lead to the EU’s reframing of climate policy. HI allows for the 2022 Energy Crisis, the growing global competition, the rising radical right, and industrial lobbying to be examined as critical junctures, thus disruptive points that challenged the established environment-first narrative. By combining HI and DI, this thesis can examine how and why the EU’s discursive shift towards an “economy-first” framing happened.

Research Design and Methodology

This thesis adopts the research design of a qualitative single case study. A qualitative research design has been selected, since this research investigates discursive data instead of quantitative data to determine the relationship between the variables, as noted by Halperin and Heath (2020, p. 13). Furthermore, a single case study will be employed, since these are often applied to investigate the existence and compositions of causal mechanisms rooted in established theories through process tracing (pp. 167-168).

Case Selection

Within the context of this thesis, a crucial case has been selected. According to Blatter (2012, p. 28), a crucial case is a case chosen based on its strong expected likelihood to confirm or contradict theoretical expectations. The author states that crucial cases are being used to strengthen or weaken the validity of theories in scientific discourse (pp. 23-24). Crucial cases are further distinguishable between most-likely and least-likely cases. Blatter (2012, pp. 23-24) describes the latter as cases in which a certain phenomenon is expected not to occur based on contextual conditions. If the phenomenon occurs nevertheless, the theory can be considerably strengthened as a result, since it has been proven under unfavorable conditions.

Therefore, this thesis investigates a least-likely critical case. Over the past few years, the European Union has globally adopted a key role in climate mitigation leadership (Sanahuja, 2025, p. 343; Siddi, 2020, p. 4), thus representing a case in which a shift away from a climate-centered narrative is least likely. The EU’s wide acknowledgment as a normative power in global climate governance (Von Lucke et al., 2021, p. 9) as well as its climate ambitions that are established on a legal basis (Sikora, 2021, p. 688) reflect how unexpected it is for the EU to sideline its climate principles due to economic concerns. However, the recent adoption of the Clean Industrial Deal and its accompanying shift towards an “economy first” framing of the European Green Deal indicate that political pressures have challenged this deeply embedded sustainability narrative (Adolphsen, Könneke & Schenuit, 2024, p. 2, 6). Since this shift is rather unexpected in the context of the EU, it qualifies as a least-likely case. Therefore, the expected causal mechanisms will be significantly strengthened in relevance if proven under unfavorable conditions in the EU.

Method of Analysis

Methodologically, this research project will employ process tracing (PT). It aims at tracing causal mechanisms to answer “why” and “how” questions (Blatter & Haverland, 2014, p. 59). Using PT within qualitative, in-depth single case studies enables researchers to draw conclusions about the causal mechanisms behind how outcomes are produced inside the case (Beach & Pedersen, 2011, p. 4). Thus, PT focuses on identifying and explaining the causal mechanisms that lead from the independent to the dependent variable. This methodology is particularly well suited, as it allows for an analysis of the causal mechanisms that explain why certain internal and external political pressures have led to a shift in the European Union’s climate policy framing. Moreover, this thesis applies theory-testing PT, which is especially suitable, as it enables the researcher to draw conclusions about whether a causal mechanism functions as predicted based on existing theory and literature, rather than establishing a new theory (Beach & Pedersen, 2019, p. 192).

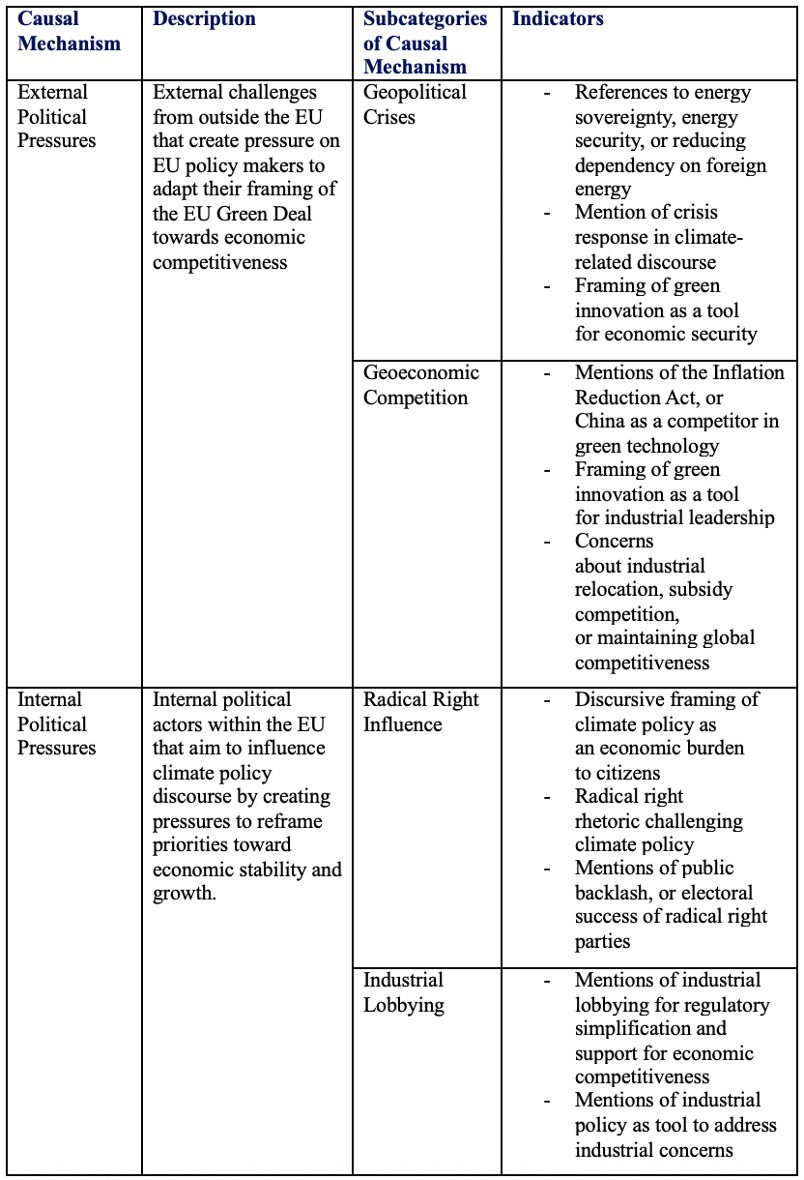

Furthermore, as a method of analysis, qualitative content analysis (QCA) will be applied to establish links between key events and the shift in the EU’s policy framing. It allows researchers to analyze the values and positions of institutional actors within textual data (Halperin & Heath, 2020, pp. 174, 376). Thus, QCA will complement PT by applying a systematic analysis of discursive shifts within textual sources, which will ultimately provide an understanding of how key events and factors have influenced the EU’s framing shift in climate governance. The data will be analyzed by systematically coding the dominant frames in policy discourse according to the (sub)categories and indicators shown below in the coding frame in Table 1. The main categories and subcategories as well as the indicators are based on the literature discussed in the theoretical framework. The analysis will allow for a determination of whether certain factors were necessary for the discursive shift to happen and whether multiple causal factors interacted to produce this outcome.

Data Selection

The data analyzed consists of a variety of documents, including speeches and statements from European Union officials, press releases, and debate sessions. These document are sourced from official websites of the European Commission and the European Parliament to ensure authenticity and relevance. Although the Council of the EU is another key institution, its debates will be excluded from this research as they are generally not accessible to the public. Moreover, it is important to note that more documents from the Commission have been selected than from the EP, due to availability. Notably, the EP debate transcripts are only published in their original languages; hence, they have been translated using Google Translate for the purpose of this thesis. These factors create limitations for this study, possibly impacting its results.

According to Collier, “process tracing requires finding diagnostic evidence that provides the basis for descriptive and causal inference” (2011, p. 824). As such, documents are selected based on their relevance to both the causal factors and the observed shift in policy framing. The selected data includes institutional discourse that reflects responses to geopolitical developments, political contestation, and industrial lobbying, which consequently allows for a relevant investigation of the research question.

Furthermore, this study will examine a timeframe from December 2019 until April 2025, beginning with the launch of the European Green Deal and continuing through the implementation of the Clean Industrial Deal. This timeframe captures the EU’s shift in discourse surrounding the EGD as well as moments of heightened political pressures, thus allowing for the examination of discursive changes in response to political pressures. However, it is of importance to note that the documents, which have been selected based on the theory-driven source selection method by Collier (2011), are concentrated in the time frame between 2023 and 2025, leading to a temporal imbalance in the data. This is because the framing shift only began to emerge during this later timeframe, making these documents significantly more relevant than earlier ones.

Results and Analysis

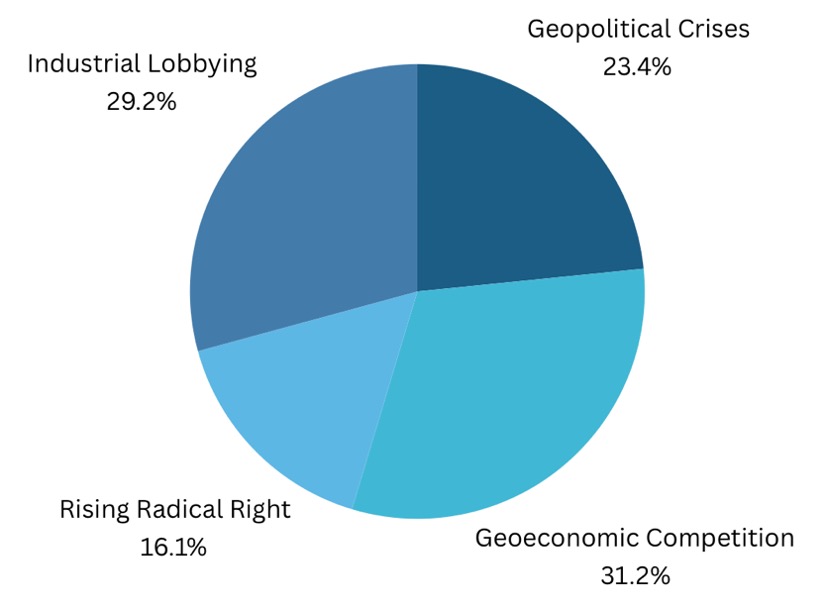

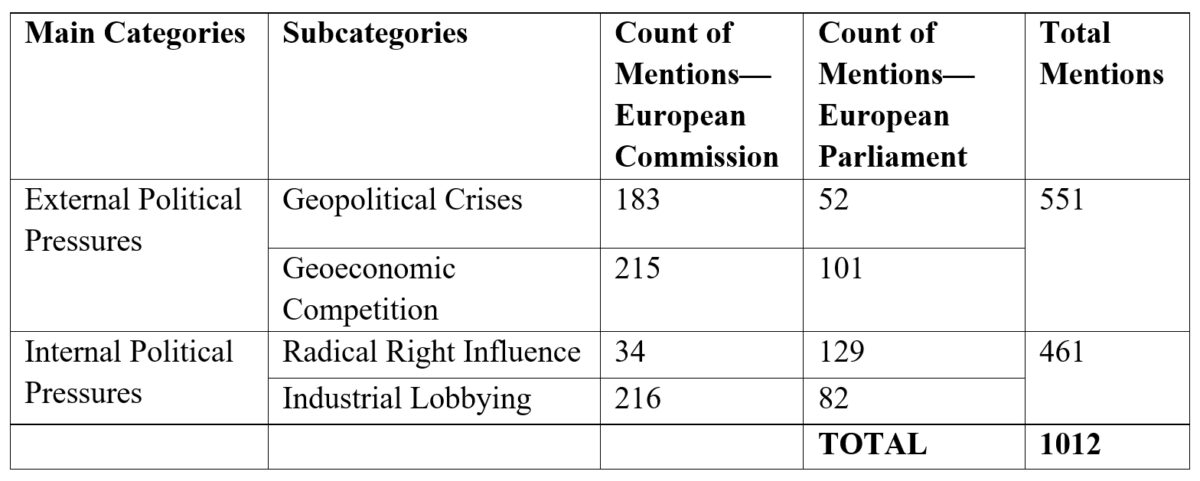

In this section, the empirical data extracted from the documents will be evaluated and analyzed to investigate whether the observed causal mechanisms function like the hypothesized ones in Figure 1. The findings (as shown in Table 2) show the amount of mentions of both causal mechanisms and their subcategories, enabling a tracing of the mechanisms within the documents. Moreover, the observed distribution of mentions of each subcategory is illustrated in Figure 1. This section is structured around the two identified causal mechanisms, beginning with the two external political pressures, geopolitical crises and geoeconomic competition, followed by the two internal political pressures, the rise of the radical right and industrial lobbying.

External Political Pressures

As previously explained in the theoretical framework, external political pressures, such as i) geopolitical crises and ii) geoeconomic competition, are hypothesized to trigger a shift in the European Union’s climate policy discourse, by heightening concerns about energy sovereignty, industrial relocations, and foreign economic competition. Thus, there should be textual evidence in line with the indicators of the coding frame if this causal mechanism works as hypothesized.

i). Geopolitical Crises

As shown in Table 2, mentions aligning with the causal mechanism triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its ensuing Energy Crisis in 2022 have been found 183 times in documents by the European Commission and 52 times in debates by the European Parliament, amounting to 235 mentions in total. Despite ranking third in quotation frequency with 23.4%, as shown in Figure 2, this subcategory has played a critical role in shaping the European Union’s discursive shift towards economic competitiveness, displayed by the nonetheless prominent mentions throughout the analyzed material.

The mechanism behind this shift can be understood through a clear causal chain divided into four key phases. The causal mechanism began with the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which revealed the EU’s strong vulnerability in energy security, due to its heavy dependence on imported fossil fuels from Russia. As Ursula von der Leyen noted, “Putin cut us off the gas supplies, we were heavily dependent on Russian gas supplies. We had skyrocketing prices for energy over a certain time—tenfold partially” (European Commission, 2025f, p. 2). This statement clearly highlights the EU’s vulnerability caused by dependence on Russian fossil fuels. Likewise, Commissioner Simson claimed that “the war in Ukraine highlighted the dangers of dependency on an unreliable supplier and the need to establish our strategic autonomy in energy resources” (European Commission, 2024h, p. 2). This marked a strategic awakening prompted by the crisis, as the European Green Deal’s energy transition could no longer be seen as separate from autonomy matters. It aligns with Goldthau and Youngs’ (2023, p. 121) observation that the Energy Crisis has highlighted the EU’s need for energy autonomy and a decrease of energy vulnerability. Hence, the crisis can be viewed as a critical juncture, as defined by Capoccia (2015, p. 148), since this moment redefined the green energy transition from an exclusively environmental to a geopolitical and existential issue for the EU, triggering a fundamental rethinking of its energy and climate policy.

The next phase of this causal mechanism involves the EU’s initial response to the Energy Crisis. In this phase the EU implemented the REPowerEU plan and worked on diversifying its energy supply, from which a substantial portion came from increasing European renewable energy supplies. This phase becomes apparent in Commissioner Simson’s statement that “when Russia invaded Ukraine and sent our energy markets into turmoil, we built on the work we had already started. We decided to fast-forward the clean energy transition” (European Commission, 2024h, p. 3). Moreover, Commissioner Simson explicitly links the initial shock to the EU’s policy response by stating that they “particularly encourage all Member States to make use of the new REPowerEU provisions to end Putin’s access to our energy markets as soon as possible” (European Commission, 2024n, p. 2). As shown in these quotes, the EU reframed renewables as not only a climate tool but also a strategic necessity for achieving energy security and autonomy. This finding aligns with Fabra’s (2023, p. 4) claim that the need to stabilize energy prices has prompted the EU to develop a policy response, which strategically reframes the EGD’s green energy transition into a tool to achieve economic and energy stability.

In the following phase, discourse within the EU institutions evolved from primarily framing energy stability as a security issue to increasingly linking it with economic competitiveness. This shift can be illustrated by several quotes from the Commission/EP. For instance, it is being highlighted that the EU’s “competitiveness depends on achieving low and stable energy prices” (European Commission, 2025o, p. 2). This statement underlines how the high cost and insufficient supply of energy in the EU have become major obstacles to European industry and its competitiveness. Commissioner Breton adds that the EU is “ensuring that decoupling from Russian fossil fuels and reaching [their] ambition of becoming a climate-neutral continent by 2050 does not compromise [their] security of supply and is underpinned by a competitive industry…” (European Commission, 2023b, p. 1), illustrating that climate policy is no longer portrayed as a trade-off between sustainability and growth, but rather as a means to achieve both. This discursive transformation reflects Schmidt’s (2008, p. 322) claim that political actors use speech to construct, dispute, and justify institutional policy narratives. As reflected in the quotes, Commissioners strategically used discourse to reframe the EGD’s aims, placing competitiveness as a legitimate and necessary core of climate governance.

The last phase shows how discourse about energy security has been fully integrated into the EU’s broader aim for economic competitiveness within the Clean Industrial Deal. For example, Member of Parliament (MEP) Antonio Decaro stated that “the Clean Industrial Deal is a European response to the energy and economic blackmail to which we have been subjected” (European Parliament, 2025b, p. 10, translation mine), clearly linking the triggering event to the official policy change. Moreover, Commissioner Séjourné pointed out that “in reality, since the war in Ukraine and the end of low-cost Russian gas supplies, [the EU’s] decarbonization strategy has become an economic strategy, since [it] must produce energy on [its] continent while reducing the risks associated with third countries” (European Parliament, 2025b, p. 22). This statement demonstrates how the EU has redefined decarbonization as a key component of economic strategy, linking energy security directly to industrial competitiveness within the CID. This development aligns with Hermwille et al.’s (2025, p. 5) claim that the CID acts as a strategic and pragmatic response to external political pressures, in this case the 2022 Energy Crisis.

ii). Geoeconomic Competition

As displayed in Table 2, the causal mechanism referring to growing geoeconomic competition as triggering event for the European Union’s framing shift of the European Green Deal has been mentioned 316 times in total, from which 215 mentions stem from the Commission and 101 mentions stem from the EP. Thus, as shown in Figure 2, geoeconomic competition is the most frequently mentioned triggering event for the EU’s framing shift with 31.2%, showing that the EU views it as the primary driver in the reshaping of their environmental policy.

Similarly to the previous subcategory’s causal mechanism, this one can be divided into four distinct phases. As previously hypothesized by Kleimann et al. (2023, p. 3421) and Cornillie et al. (2024, p. 4), the first signs of threatening economic competition from other countries appeared with the announcement of the Inflation Reduction Act as well as growing awareness of China’s dominance in clean technology industries. This initial awareness is reflected by Ursula von der Leyen, saying that “we have observed that China, over the last 20 to 30 years, has strategically bought mine after mine globally. They take the raw material, they have the processing procedures in China and then they have the monopoly…” (European Commission, 2024f, p. 2). This statement reflects Martini et al.’s (2024, p. 9) assertion that the growing economic global competition has created a sense of urgency amongst EU leaders, culminating to another critical juncture as defined by Capoccia (2015, p. 148).

In response to the perceived threats, EU institutions began to frame the EGD’s clean industry and green technology not simply as a solution for decarbonization, but increasingly as a crisis of industrial competitiveness that requires urgent action. This shift is driven by concerns that without a clear and assertive strategy, the EU could lose out economically on the green transition. For instance, Commissioner Šefčovič warned, that “EU industry must get rapid and effective relief when faced with dumped or unfairly subsidised imports, non-market overcapacities, or negative spillovers from foreign industrial policies” (European Commission, 2024u, p. 2). Commissioner Breton further emphasized that “without an industrial plan, there is a risk that [the EU is] creating a new market but actually handing that booming market—and related jobs—to others” (European Commission, 2023b, p. 1). This shift in framing clearly aligns with Entman’s (1993, p. 52) Framing Theory, in which political actors strategically emphasize certain problems, in this case industrial competition, to justify new policy directions.

Within the next phase EU institutions began revising its environmental policy focusing on industrial protection from unfair global competition, by leveling the playing field. As part of this revision, the Commission declared that they “will act even more decisively to protect [their] industries from unfair global competition and overcapacities through a range of Trade Defence and other instruments” (European Commission, 2025s, p. 2). In this context, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) has been revised to not only serve as a tool to reduce emissions, but also to safeguard European industry from geoeconomic competition and ensure the European industry’s competitiveness in the green tech race. As announced by the Commission, “to preserve an international level playing field, [it] will also carefully monitor the effectiveness of CBAM implementation and take action” (European Commission, 2025p, p. 2).

In the final phase, competitiveness framing has definitively been absorbed in the EU’s framing of the EGD. The climate policy is no longer framed primarily as a response to the climate crisis, but with the adoption of the Clean Industrial Deal it has become a strategy for industrial leadership. Referring to the oversaturation of markets by Chinese clean technology products and the accompanying decreased demand, the Commission concludes that “this is why the Clean Industrial Deal aims at creating the right conditions for the industry to invest and produce in the EU, namely by driving down energy prices and boosting demand for clean products” (European Commission, 2025r, p. 1). This marks a fundamental reframing of the EU’s climate policy as a geoeconomic tool, in line with Hermwille et al.’s (2025, p. 5) reflection that the CID is a strategic policy response to external political pressures.

Internal Political Pressures

Similar to the external political pressures, internal political pressures such as i) the rising radical right and ii) industrial lobbying are also hypothesized to lead to a shift in the European Union’s climate policy discourse, by politicizing climate change, engaging with interest groups, undermining institutions, and lobbying. Therefore, the textual evidence should match with the coding frame’s indicators if this causal mechanism works as hypothesized.

i). Rise of the Radical Right

Table 2 shows that mentions that are in line with the causal mechanism triggered by the rising radical right have appeared 163 times in total, from which only 34 mentions were found in the Commission’s documents, whereas 129 mentions were found in Parliamentary debates, making this the least prominent subcategory of the causal mechanisms with 16.1%, as reflected in Figure 2.

The first phase of this causal mechanism aligns with Mudde’s (2024, pp. 126-130) findings as it began with the electoral gain of the radical right political groups during the 2024 European Parliament elections, which again can be classified as another critical juncture as defined by Capoccia (2015, p. 148). Reflecting Yazar and Haarstad’s (2023, pp. 8-9) findings, this electoral success gave the extreme right greater visibility within a European Union context, enabling them to discursively delegitimize the European Green Deal, framing it as an elitist agenda that threatens national industry and is detached from the citizens’ struggles. Evidence for this phase can be found within parliamentary debates, where, for instance, Member of Parliament Ivan David (ESN) contested that “the absurd Green Deal project is based on fraud and is already today, when not all its idiotic ideas have been implemented, destroying the economies of the European Union countries and with it the social conditions of the majority of citizens” (European Parliament, 2024b, p. 7, translation mine).

In the second phase, extreme right MEPs increasingly began linking the EGD’s effects to competitiveness, portraying it as the root cause for the EU’s economic decline. Within this phase, the EGD is no longer only criticized as a burden to citizens and industry but additionally framed as a structural threat to European competitiveness and economic stability. Thus, this phase is consistent with Ćetković and Hagemann’s (2020, p. 3, p. 5) discovery that the radical right’s anti-green narrative is centered around economic issues. A recurring theme amongst radical right MEPs was that the EU’s climate policy undermines its capacity to compete internationally, going so far as to tell the Commission to “finally face reality: Restoring competitiveness is only possible without a Green Deal! And therefore, put an end to this green disaster” (European Parliament, 2024b, p. 11, translation mine). This statement among similar ones increased pressure on the Commission to revise the EGD in terms that prioritize economic resilience and competitiveness.

In response to this growing polarization, the third phase involved a strategic adaptation of discourse amongst Commissioners. Despite continuously emphasizing climate goals, an increasing shift towards a prioritization of the economy and prosperity for its citizens can be observed in the textual data. As Commissioner Šefčovič stated, the Commission does “recognise the legitimate concerns of citizens and industry over the costs of the transition” (European Commission, 2024c, p. 1), and that they “remain committed to continue supporting themthrough [their] policy and regulatory measures as well as funding instruments” (European Commission, 2024c, p. 1). However, the small number of mentions regarding this mechanism within the Commission, as shown in Table 2, suggests a strategic balancing act, in which the Commission aims to reaffirm the EGD’s legitimacy by integrating themes of industrial competitiveness and social prosperity, whilst delegitimizing extreme right influence through statements such as the anti-green wave being “a clear attempt to divide and polarise [the EU’s] societies” (European Commission, 2024r, p. 1). This again clearly reflects Entman’s (1993, p. 52) Framing Theory, as the Commission frames issues to downplay opposition and center competitiveness to re-legitimize the EGD.

Lastly, in the outcome phase the Commission’s climate discourse consolidated competitiveness as a central element to the EGD. This development is evident in the adoption of the Competitiveness Compass and the Clean Industrial Deal, which explicitly create a linkage between climate goals and competitiveness. The Commission especially highlighted that the CID will be shaped by “a series ofclean transition dialogues with key industrial sectors…” (European Commission, 2024c, pp. 1-2), and that they “are seeking to expand and intensify outreach to citizens” (European Commission, 2024c, p. 2), reflecting the Commission’s effort to build societal support and mitigate oppositional pushes, by aligning the new CID with the interests of industry and citizens.

ii). Industrial Lobbying

Finally, the causal mechanism triggered by industrial lobbying has 216 observed mentions within the Commission and 82 within the European Parliament, as shown in Table 2, which accumulates to 298 total mentions. Thus, as illustrated by Figure 2, it is the second most referred to subcategory of the causal mechanisms with 29.2%.

The trigger phase of this causal mechanism began with the energy-intensive and export-oriented European industries raising concerns about decreased demand caused by unfair global competition and excessive bureaucracy under the European Green Deal, warning that it could lead to deindustrialization. As Commissioner Séjourné highlighted, “businesses and their employees all tell us: we have made efforts to decarbonize our industries and businesses, but there is not enough demand” (European Parliament, 2025b, p. 1, translation mine). Moreover, “[the European industries] are asking for simplification, they are asking for less bureaucracy, they are asking for more listening” (European Parliament, 2025b, p. 3, translation mine). These claims clearly converge with Bhandari and Dijkstra’s (n. d., p. 15) findings, as the European industry framed the European Union’s climate policy not as a necessary transition, but as a competitive disadvantage, ultimately creating lobbying pressure for regulatory simplification.

The textual evidence shows that, in response to the industrial lobbying, the Commission began to take up the industry’s concerns in their discourse, which marks the second phase of this mechanism. Statements such as “we will work on the acceleration of permitting. You know that this is a constant complaint, rightly so” (European Commission, 2025f, p. 2) and “we must do it in a way that ensures that our companies retain their competitiveness at the global level. That our industry can stay, and thrive, and prosper, here in Europe” (European Commission, 2024p, p. 1) show how the Commission aligns their discourse with business priorities, revealing its willingness to prioritize competitiveness. The trend shows increasing mentions of prioritizing predictability, simplifying regulatory burdens, and holding strategic dialogues with industrial stakeholders.

Within the third phase a policy response was issued, which translated the discursive acknowledgement of competitiveness and regulatory issues into concrete institutional action. As the Commission points out, “to enable the greening and competitiveness of [its] industry, and the investments in the transformation of [its] economy, the Commission has already provided a clear policy framework with ambitious regulation” (European Commission, 2023a, p. 1). Central to this development were the Omnibus legislations, the Net-zero Industry Act, and the Clean Industrial Deal, which were implemented “to cut the ties that still hold [the EU’s] companies back and make a clear business case for Europe” (European Commission, 2025s, p. 1). These initiatives respond directly to the industry’s call for regulatory relief and the provision of certainty. They also exemplify how institutions, in this case the Commission, use discourse to justify new policy courses, such as the CID prioritizing the economy (Schmidt, 2008, p. 322). Therefore, this phase reflects a transition towards industrial and economic support and away from regulation for climate mitigation.

The final phase of this causal mechanism displays the outcome, which is a discursive and institutional reframing of EU climate policy as industrial strategy. The Commission stated that the CID and the Omnibus legislations are their “business plan for Europe and [their] roadmap for turbo-charging [their] competitiveness and [their] economy. It responds to a loud and clear call from industries across Europe” (European Commission, 2025af, p. 1), positioning itself less as a climate regulator and more as a partner for businesses and industry. Although climate goals remain on the EU’s agenda within the CID, they are now embedded within a broader narrative of economic stability and competitiveness, showcasing the sustained lobbying efforts. This finding confirms Knill and Liefferink’s (2013, p. 119) concept of multi-level governance, as the EU’s climate policy has become subjected to the lobbying of European interest groups.

Interdependence of Causal Mechanisms

This thesis interprets the previously analyzed causal mechanisms not as isolated processes, but as interdependent and mutually reinforcing. While the external political pressures, namely the 2022 Energy Crisis and the growing geoeconomic competition, created the right conditions for a shift in climate policy within the European Union, these pressures appear to have gained political momentum mostly because the previously discussed internal actors mobilized them to pursue their own agendas. Building on Potters and van Winden’s (1990, p. 64) observation that external political pressures are oftentimes mediated through internal actors, this interpretation goes even further by viewing it as a dynamic feedback loop. Evidence suggests that radical right actors leveraged the Energy Crisis and geoeconomic competition to delegitimize the European Green Deal, by portraying it as detached from the economic realities of citizens and industries (European Parliament, 2025b, p. 7). Similarly, industrial lobbyists aligned their demands with the issues of fiercer global competition and high energy prices, thus framing external shocks as justifications for their demands of regulatory simplification and a more supportive industrial policy (European Commission, 2025j, p. 1). These developments are seen here as part of a political dynamic feedback loop, in which external political pressures fuel internal contestations of the EGD and internal political pressures amplify the feeling of urgency caused by external political pressures. Therefore, rather than viewing the EU’s shift towards an “economy-first” framing of the EGD as individual responses to the two causal mechanisms, this thesis argues that it can better be understood as the result of strategic political interaction. Recognizing this interdependence allows for a more comprehensive understanding of how and why the EU’ climate policy narrative evolved during this specific period.

Moreover, it can be said that the findings closely align with the combined theoretical lens of discursive and historical institutionalism. Through a discursive institutionalist lens, as provided by Schmidt (2008, pp. 306, 322), it becomes evident that EU actors, especially the Commission, strategically reframed the EGD through shifting towards a narrative of economic competitiveness and stability. This policy change and shift in institutional priorities did not merely reflect changing circumstances, but also the power of ideas and discourse. Meanwhile, through the lens of historical institutionalism, as outlined by Capoccia (2015, p. 147), it becomes evident why this shift occurred at this specific moment. The 2022 Energy Crisis, growing international competition, the rising radical right, and industrial lobbying manifested as critical junctures and disrupted the existing policy path. These critical junctures created a window for a reframing of the EGD reinforced by institutional change, namely the Clean Industrial Deal. Combined, these two theoretical lenses show how discourse and critical junctures have jointly produced a transformation in EU climate policy.

Conclusion and Reflection

This thesis examined how internal and external political pressures have influenced the European Union’s shift in climate policy framing to an “economy-first” narrative since the implementation of the European Green Deal. To answer the research question: Internal and external political pressures caused the EU’s framing shift in climate policy, by creating political demands that prioritized economic concerns over environmental ones and by generating a sense of urgency around economic competitiveness.

Externally, political pressures, such as the 2022 Energy Crisis and growing competition from the US and China, established a feeling of urgency regarding economic autonomy and competitiveness, legitimizing a discursive shift that frames these concerns as central goals of climate policy. Internally, political pressures, such as the rising radical right and industrial lobbying, transformed public and industrial discontent into political demands. These actors politically leveraged the external pressures, reinforcing the urgency to respond, and advocated for policy responses that prioritized competitiveness, economic protection, and regulatory simplification. Thus, as revealed by the analysis, the two expected causal mechanisms are present but nevertheless interdependent, creating a feedback loop. Ultimately, the reframing positioned the EGD as a tool to achieve economic stability, autonomy, and competitiveness, rather than as a primary response to climate change.

The discursive shift has important implications for the future of the EU’s climate governance. The increasing prioritization of economic stability and competitiveness may influence the implementation of climate initiatives beyond the term of the current Commission. For example, although this framing helps ensure public and industrial support for the EGD, it also risks neglecting climate mitigation at a time when a green transition is crucial. Ultimately, the EU must find a balance between climate ambition and economic security.

As outlined in the methodology, this thesis has certain limitations. Firstly, the analysis excludes discourse from the Council of the EU, since these documents are not publicly accessible. Moreover, the timeframe of the analysis focuses on documents between 2023 and 2025, as this was the period during which the discursive shift became most explicit in institutional discourse. While this temporal scope allows for an in-depth analysis of the critical moments, it limits an examination of long-term developments. Lastly, a key limitation regards generalizability. The results are not directly applicable beyond this specific EU context, as the identified causal mechanisms are highly specific to the EU’s institutional structure and geopolitical position.

Therefore, future research could build on this thesis by addressing these limitations. This could be by including discursive documents from the Council of the EU, as another key institution. Documents from national governments and civil society could also enrich the findings, by further illustrating how climate policy is framed across the multi-level governance system of the EU. Moreover, future longitudinal studies examining whether the shift towards an “economy-first” framing persists after 2029, beyond this Commission’s term, would be valuable in assessing the durability. Lastly, this research could benefit in generalizability from future comparative studies exploring similar internal and external political pressures and their impacts on other global actors.

Figures and Tables

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Speeches and statements from the European Commission Press Corner. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/home/en. Passages cited include the following:

European Commission. (2023a, February 1). Questions and Answers: Green Deal Industrial Plan for the Net-Zero Age. [Q&A]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_23_511

European Commission. (2023b, February 1). No Green Deal without strong European clean tech manufacturing I Blog of Commissioner Thierry Breton. [Statement]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_23_530

European Commission. (2024c, February 6). Press remarks by Executive Vice-President Šefčovič and Commissioners Simson and Hoekstra on the Communications on a recommended emissions reduction target for 2040 and Industrial Carbon Management. [Speech transcript]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_24_673

European Commission. (2024f, February 22). Opening speech by President von der Leyen at the Clean Tech Industry Dialogue. [Speech transcript]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_24_977

European Commission. (2024h, April 8). Speech by Commissioner Simson at the National Press Club of Australia. [Speech transcript]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_24_1883

European Commission. (2024n, May 21). European consumers and industry to benefit from clean, secure and stable energy supplies with key market reforms now adopted. [Press release]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_2261

European Commission. (2024p, June 13). Speech by Executive Vice-President Šefčovič at the opening of the Eurochambres Congress 2024. [Speech transcript]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_24_3261

European Commission. (2024r, July 18). Statement at the European Parliament Plenary by President Ursula von der Leyen, candidate for a second mandate 2024-2029. [Statement]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_24_3871

European Commission. (2024u, November 4). Confirmation hearing of Maroš Šefčovič, Commissioner-designate for Trade and Economic Security, and Interinstitutional Relations and Transparency. [Speech transcript]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_24_5663

European Commission. (2025f, January 29). Statement by President von der Leyen on the EU Competitiveness Compass. [Statement]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_25_364

European Commission. (2025j, February 5). Keynote speech by Commissioner Jørgensen at Financial Times-Iberdrola International Energy Policy Forum 2025. [Speech transcript]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_25_425

European Commission. (2025o, February 18). Commissioner Tzitzikostas speech at the Transport & Environment event From the Green Deal to the Clean Industrial Deal. [Speech transcript]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_25_525

European Commission. (2025p, February 25). Concept Note: Strategic Dialogue on Steel. [Announcement]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ac_25_612

European Commission. (2025r, February 26). Questions and answers on the Clean Industrial Deal. [Q&A]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_25_551

European Commission. (2025s, February 26). A Clean Industrial Deal for competitiveness and decarbonisation in the EU. [Press release]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_550

European Commission. (2025af, March 10). Commissioner Roswall’s speech at the Nordic Forum on raw materials – Clean Industrial Deal and the Nordic Raw Materials Sector. [Speech transcript]. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_25_736

Verbatim reports of European Parliament proceedings. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/portal/en. Reports cited are the following:

European Parliament. (2024b, December 18). Restoring the EU’s competitive edge—the need for an impact assessment on the Green Deal policies (topical debate). [Debate transcript]. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/CRE-10-2024-12-18-ITM-013_EN.html

European Parliament. (2025b, March 11). Clean Industrial Deal (debate). [Debate transcript]. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/CRE-10-2025-03-11-ITM-014_EN.html

Secondary Sources

Adolphsen, O., Könneke, J., & Schenuit, F. (2024). Die internationale Dimension Europäischer Klimapolitik: Eine Strategie zur Verzahnung von interner und externer Dimensionen. Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 67, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.18449/2024A67

Bartolini, S. (2024). Actors and structures in politics. Quaderni dell Osservatorio Elettorale QOE—IJES, 87(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.36253/qoe-16765

Beach, D., & Pedersen, R. B. (2011, September 1-4). What is Process Tracing actually tracing?: The three variants of process tracing methods and their uses and limitations. Paper presented at the American Political Science Association Annual Meeting, Seattle, United States (pp. 1-35). [PUBLISHED DIGITAL PAPER]

Beach, D., & Pedersen, R. B. (2019). Process-Tracing methods: Foundations and guidelines (1st ed.). University of Michigan Press.

Bhandari, S., & Dijkstra, A. M. (n.d.). Interest groups and the European Green Deal.

Blatter, J. (2012, February). Innovations in case study methodology: Congruence analysis and the relevance of crucial cases. In Annual Meeting of the Swiss Political Science Association, Lucerne (pp. 1-32). [PUBLISHED DIGITAL PAPER]

Blatter, J., Haverland, M. (2014). Case studies and (causal-) process tracing. In I. Engeli & C. R. Allison (Eds.), Comparative policy studies: Conceptual and methodological challenges (pp. 59-83). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137314154_4

Capoccia, G. (2015). Critical junctures and institutional change. In J. Mahoney & K. A. Thelen (Eds.), Advances in comparative-historical analysis (pp. 147-179). Cambridge University Press.

Chateau, J., Miho, A., & Borowiecki, M. (2023). Economic effects of the EU’s ‘Fit for 55’ climate mitigation policies: A computable general equilibrium analysis. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, 1775, 1-33. https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/f1a8cfa2-en

Ćetković, S., & Hagemann, C. (2020). Changing climate for populists? Examining the influence of radical-right political parties on low-carbon energy transitions in Western Europe. Energy Research & Social Science, 66, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101571

Cohen, B. J. (1990). The political economy of international trade. International Organization, 44(2), 261–281. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081830003527X

Collier, D. (2011). Understanding process tracing. PS: Political Science & Politics, 44(4), 823-830. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096511001429

Cornillie, J., Delbeke, J., Egenhofer, C., Pandera, J., & Tagliapietra, S. (2024). A Clean Industrial Deal delivering decarbonisation and competitiveness. European University Institute, 28, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.2870/4930238

Cornillie, J., Delbeke, J., Egenhofer, C., Iozzelli, L., Mackowiak Pandera, J., & Tagliapietra, S. (2025). Implementing the Clean Industrial Deal and strengthening Europe’s economic resilience. European University Institute, 06, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.2870/9051196

Domorenok, E., & Graziano, P. (2023). Understanding the European Green Deal: A narrative policy framework approach. European Policy Analysis, 9(1), 9-29. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1168

Eckert, S. (2021). The European Green Deal and the EU’s regulatory power in times of crisis. Journal of Common Market Studies., 59(S1), 81-91. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13241

Eckert, E., & Kovalevska, O. (2021). Sustainability in the European Union: Analyzing the discourse of the European Green Deal. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(2), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14020080

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51-58.

Fabra, N. (2023). Reforming European electricity markets: Lessons from the energy crisis. Energy Economics, 126, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2023.106963

Fetting, C. (2020). The European Green Deal. ESDN Report, 2(9), 1-22.

Gerken, J. (2023). The European Green Deal, its narrative of green politics for the next generation and the EU’s search for a stable telos. Culture, Practice & Europeanization, 8(1), 127-151. https://doi.org/10.5771/2566-7742-2023-1-127

Goldthau, A. C., & Youngs, R. (2023). The EU energy crisis and a new geopolitics of climate transition. Journal of Common Market Studies, 61(S1), 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13539

Gullberg, A. T. (2008). Lobbying friends and foes in climate policy: The case of business and environmental interest groups in the European Union. Energy Policy, 36(8), 2964-2972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2008.04.016

Halperin, S., & Heath, O. (2020). Political research: Methods and practical skills. Oxford University Press.

Hermwille, L., Leipprand, A., Kiyar, D., Ruß, M., Hullmann, C., Elsner, C., Xia-Bauer, C., Obergassel, W., Berg, H., Wilts, H., Thomas, S., Samadi, S., & Fischedick, M. (2025). Rapid assessment of the Clean Industrial Deal: An initial assessment of the EU Commission’s industrial policy work programme for 2025-2029. Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.48506/opus-8789

Jesus, A. M. D. (2010). Policy-making process and interest groups: How do local government associations influence policy outcome in Brazil and the Netherlands? Brazilian Political Science Review, 4(1), 69-101. https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-3867201000010003

Kangas, O. E., Niemelä, M., & Varjonen, S. (2014). When and why do ideas matter? The influence of framing on opinion formation and policy change. European Political Science Review, 6(1), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773912000306

Kleimann, D., Poitiers, N., Sapir, A., Tagliapietra, S., Véron, N., Veugelers, R., & Zettelmeyer, J. (2023). Green tech race? The US Inflation Reduction Act and the EU Net Zero Industry Act. The World Economy, 46(12), 3420-3434. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13469

Knill, C., & Liefferink, D. (2013). Policy-making, implementation and patterns of multi-level governance. In C. Knill & D. Liefferink (Eds.), Environmental politics in the European Union, 102-120. Manchester University Press. https://doi.org/10.7765/9781847792204

Leichter, J., Mocci, C., & Pozzuoli, S. (2010). Measuring external competitiveness: An overview. Government of the Italian Republic, Ministry of Economy and Finance, Department of the Treasury Working Paper, (2), 1-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1628111

Martini, L., Görlach, B., Kittel, L., Sultani, D., & Kögel, N. (2024). Between climate action and competitiveness: Towards a coherent industrial policy in the EU. Ecologic Institute, 9-51.

Milner, H. V. (1988). Resisting protectionism: Global industries and the politics of international trade. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691225289

Mudde, C. (2024). The 2024 EU elections: The far right at the polls. Journal of Democracy, 35(4), 121-134. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2024.a937738

Niemann, A. (2006). Explaining decisions in the European Union (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511492044

Otteni, C., & Weisskircher, M. (2022). Global warming and polarization: Wind turbines and the electoral success of the greens and the populist radical right. European Journal of Political Research, 61(4), 1102-1122. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12487

Potters, J., & Van Winden, F. (1990). Modelling political pressure as transmission of information. European Journal of Political Economy, 6(1), 61-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/0176-2680(90)90036-I

Sanahuja, J. A. (2025). Green deal and new developmentalism. In J. A. Sanahuja & R. Domínguez (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of EU-Latin American Relations (pp. 335-351). Palgrave Macmillan.

Schlichting, I. (2013). Strategic framing of climate change by industry actors: A meta-analysis. Environmental Communication: A Journal of Nature and Culture, 7(4), 493-511. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2013.812974

Schmidt, V. A. (2008). Discursive Institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Annual Review of Political Science, 11(1), 303-326. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060606.135342

Sgaravatti, G., Tagliapietra, S., & Zachmann, G. (2023). Adjusting to the energy shock: The right policies for European industry. Bruegel Policy Briefs, 11, 1-21.

Siddi, M. (2020). The European Green Deal: Asseasing its current state and future implementation. Upi Report, 114, 1-14.

Sikora, A. (2021). European Green Deal – Legal and financial challenges of the climate change. ERA-Forum, 21(4), 681–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12027-020-00637-3

Stefanis, C., Stavropoulos, A., Stavropoulou, E., Tsigalou, C., Constantinidis, T. C., & Bezirtzoglou, E. (2024). A spotlight on environmental sustainability in view of the European Green Deal. Sustainability, 16(11), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114654

Stoian, I. C., Clipa, R. I., Ifrim, M., & Lungu, A. E. (2023). Perception regarding European Green Deal challenges: From environment to competition and economic costs. E&M Economics and Management, 26(3), 4-19. https://doi.org/10.15240/tul/001/2023-3-001

Timofejevs, P. F. (2020). The environment and populist radical right in Eastern Europe: The case of national alliance 2010-2018. Sustainability, 12(19), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198092

Von Lucke, F., Diez, T., Aamodt, S., & Ahrens, B. (2021). The EU and global climate justice: Normative power caught in normative battles. Routledge.

Yazar, M., & Haarstad, H. (2023). Populist far right discursive-institutional tactics in European regional decarbonization. Political Geography, 105, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2023.102936

Further Reading on E-International Relations